- Retro XP

- Posts

- Retro spotlight: World Series Baseball

Retro spotlight: World Series Baseball

The game that changed everything for baseball video games, on multiple levels.

This column is “Retro spotlight,” which exists mostly so I can write about whatever game I feel like even if it doesn’t fit into one of the other topics you find in this newsletter. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

I played a whole bunch of baseball video games as a kid. It wasn’t a difficult thing to do when you had a Super Nintendo — the system was practically lousy with them. There were 21 different baseball games for the SNES, ranging from licensed to unlicensed, with real players or cyborgs, published by Nintendo themselves, or even just featuring you as a relief pitcher. Ken Griffey Jr. Presents Major League Baseball is the one I actually owned as a child who could only get so many new video games out of his parents in a year, but plenty of others popped into the house briefly as rentals.

What they tended to have in common is an arcade-style play. Exaggerated animations, fast-paced, constant pitching and swinging, and not necessarily realistic sound effects. The aforementioned Ken Griffey Jr. Presents was a masterclass in all of that, with its caricatures of players, “Oh come on!” yell at the umpire by those players, the sound the ball made as it traveled, the music, the animations. It was also representative of an era that has, at this point, practically vanished in favor of simulation and realism.

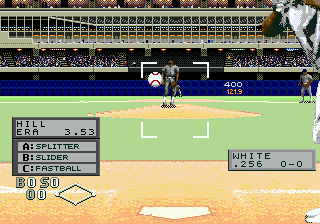

I picked up a Genesis at the tail-end of that system’s lifecycle, thanks to a cousin who was getting married and either because video games were not going to be part of his life anymore or because he was moving on to a 32-bit console. His whole collection came with it, and World Series Baseball was one of the included games. It was apparent, immediately, that this was a different baseball game than the many that I’d been exposed to by that point. You no longer had that zoomed out view from behind the plate (or, in the case of something like the Bases Loaded games, from behind the pitcher, aping how the games look on television), but instead were zoomed in, from the catcher’s point of view. You couldn’t make out the entire body of the batter, but could see him leaning over the plate, and instead of more of a top-down strike zone where left and right of the plate were the only considerations you needed to make, and you manipulated the ball’s movement and speed with the D-pad as it traveled toward the batter, you now made these decisions of pitch placement, type, and speed before ever throwing the ball, all via menus.

Image credit: MobyGames

An announcer was part of the proceedings, too, with the play-by-play commentator for the San Diego Padres, Jerry Coleman, digitized and with his phrases stitched together into something that was supposed to approximate the action on the field. There were only so many phrases, and it had the kind of stilted sound that you could expect from a Sega Genesis game slapping a collection of soundbytes together into a sentence as needed, but it was also commentary! The crowd reacted to plays, the bat was meant to sound realistic, the ball traveled with a speed that felt realistic, which allowed Coleman’s call of “He blasted it to center, way back, to the wall! It’s gone! Home run!” to feel accurate to real-life dingers in terms of how long it took to happen and what you’d expect to hear while seeing it.

The scoreboard had animations after each play, too, reacting to whether your player struck out or struck out an opponent, hit a home run, etc. Next batter info was also displayed on the scoreboard, again trying to show an air of authenticity, and the game was not only licensed by Major League Baseball itself, but also the Major League Baseball Players Association — the league and the union were not necessarily on the same page when it came to licensing in games 30-plus years ago, and given they were in active and incessant labor battles at the time where raising additional money to fight those fights was important, well, you saw a whole bunch of games that had just one license or the other. World Series Baseball on the Genesis was the first to have both, and until Triple Play ‘97 on the Playstation — released in the summer of 1996 — it was the only baseball game franchise to do so. That might not sound like that much time passing, but in those two-plus years in between the first World Series Baseball and EA’s entry in the field, over another dozen baseball non-World Series Baseball titles were released — it was truly a different time.

There were just 28 teams in MLB at the time — the Florida Marlins (now Miami Marlins) and Colorado Rockies had just been introduced to the league in 1993 — and all of them were included, along with all 700 players on the big-league rosters. Actual logos and actual stadiums were there, and while uniforms were not — one sacrifice that seems to have been made in order to get these advanced-looking and regularly large sprites into the game, along with all of the voice clips, was to have uniforms be designed like they were from a century before, with whites vs. grays — it didn’t matter all that much in the grand scheme of things, because check out how well these sprites all animated.

It’s not just that you could pick pitch type and pitch location from a menu, but there were a plethora of pitches to choose from, at least for the time. Charlie Hough and Tim Wakefield’s knuckleballs were included, as well Norm Charlton’s nasty screwball. You had a more basic (and accurate) three-pitch selection of fastball, change-up, and a breaking ball — either a curveball or a slider — for most pitchers, but depending on the pitcher, you could also have access to a split-fingered fastball, sinker, or, as mentioned, screwball or knuckler.

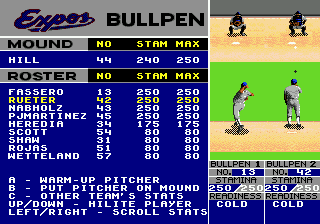

You had to think in three dimensions with your pitch location, since these balls had specific movement patterns they would follow, that would also change a bit depending on whether you chose to throw them slow, medium, or fast. A slider from a right-handed pitcher, if you want it to enter the strike zone after appearing like it was going to be a ball thrown inside, had to aim for where you wanted the break to happen — left and outside of the zone — not where you wanted it to end up. A sinker, if you want it to drop out of the strike zone, has to be located in the bottom quadrants of it somewhere, before it does its thing and “sinks” out of the zone and away from the batter’s swing. A knuckleball’s location is mostly about prayer. Velocity and location are worse as a pitcher tires — you have to use relievers here, and even warm up the pitchers in advance before you throw them in, to get maximum effectiveness from your pitching staff.

Image credit: MobyGames

You can play an Exhibition game, a Home Run Derby — that’s not a joke about how easy it ends up being to hit home runs in any game mode once you get the hang of the swing mechanics and timing, but it could be — take batting practice with specific setups for handedness and such, or start an entire season, which can be set to have the new six-division format of 1994 or the more traditional four-division setup of just East and West divisions in both of the American and National Leagues. You can also set season length to 13, 26, 52, 104, or a standard 162 games. There’s no franchise mode, but hey, it was 1994. Being able to play a full-length season was sometimes in question at this time, never mind one with all of the real players and all of the real teams in real stadiums. Difficulties range from Rookie, to Veteran, to All-Star, with higher velocities for pitches — which makes it more difficult to time them for hitting as well as locate them as a pitcher — as you go up that ladder, as well as a smaller hit box, especially as you focus on a power swing over a contact swing for the hitters. Stats are tracked within a season, and immediately, too, as their new numbers will begin to show up and update throughout the first game you play.

Now, this is all stuff that seems normal today, in a world where MLB: The Show is the dominant franchise — as well as the only licensed one, given Super Mega Baseball deals with fictional players and retired ones — and has itself existed for nearly 20 years now. World Series Baseball looks and feels pretty rudimentary in comparison to what we have available in the present, but this was a massive shift at the time — baseball games, to that point, were all working off of the same basic premise of how these titles were supposed to look and feel, with the big point of disagreement being about whether the camera should be behind the pitcher to emulate a television broadcast or not. World Series Baseball threw a literal new dimension into the mix, and essentially signaled the shift to the kinds of 3D experiences that the systems of the 32-bit era would focus on, which in turn led to even more refinement on the N64 and into the next era of consoles beyond that.

You can watch pitchers warm up in the bullpen! Image credit: MobyGames

World Series Baseball changed the game in more ways than just managing to somehow unite MLB and MLBPA licensing at a time when the two sides were, understandably, at each other’s throats. I’d get into how MLB’s owners and commissioner engineered the 1994 strike so that fans would be mad at the players instead of the owners over a work stoppage like with the 1990 lockout, but that’s a detailed conversation for my other beat — the point in this space is that the two sides agreed to something that would benefit both of them at a time when they were basically incapable of doing that anywhere, when interim commissioner Bud Selig was plotting to scale back basically everything the PA had achieved in the previous three-ish decades of collective bargaining even if he had to act in unilateral, illegal ways to pull it off, when both sides granted their license to game after game but never together, because licensing itself was part of the battlefield between the two. That’s not as immediately notable when you pop the cartridge in and hear Jerry Coleman’s voice come through your speakers, or notice how much different World Series Baseball looks and feels compared to the competition of the time — or how much it is clearly the prototype for the direction baseball video games would go — but it’s just as vital to the history and legacy of baseball video games as the rest of it.

Sega would produce a number of World Series Baseball titles. A 1995 sequel, also known as World Series Baseball, released for the Sega Saturn, and came out in Japan on the Game Gear as Hideo Nomo’s World Series Baseball. World Series Baseball ‘95 had Game Gear, Genesis, and 32X releases, with the last of those titled World Series Baseball Starring Deion Sanders. World Series Baseball ‘96 released on the Genesis and Windows, while World Series Baseball II came out for the Saturn in 1996. World Series Baseball ‘98 was also a Saturn title that somehow had a Genesis release despite it being 1997, and then the franchise would begin its shift into the 2K era, in terms of naming conventions, with the Dreamcast: World Series Baseball 2K1, 2K2, and 2K3 were the final three games in the series, with Visual Concepts handling development of the last two, which were multiplatform given Sega’s transition to third-party development and publishing. Visual Concepts was acquired by Sega in 1999, and then sold off to Take-Two Interactive after Sega exited the sports market. A disappointing end for those who loved what Sega had going on with both their Sega Sports and 2K lines.

The end doesn’t take away from what was accomplished by Sega and World Series Baseball, however. It was hugely influential in a number of ways, from the actual gameplay and its presentation to the business model behind it, and whether you have played it yourself or not, you have at least experienced its legacy in the three-plus decades since its arrival.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.